Kinship and Commons: The Bedouin Experience, THE CAMBRIDGE HANDBOOK OF COMMONS RESEARCH INNOVATIONS

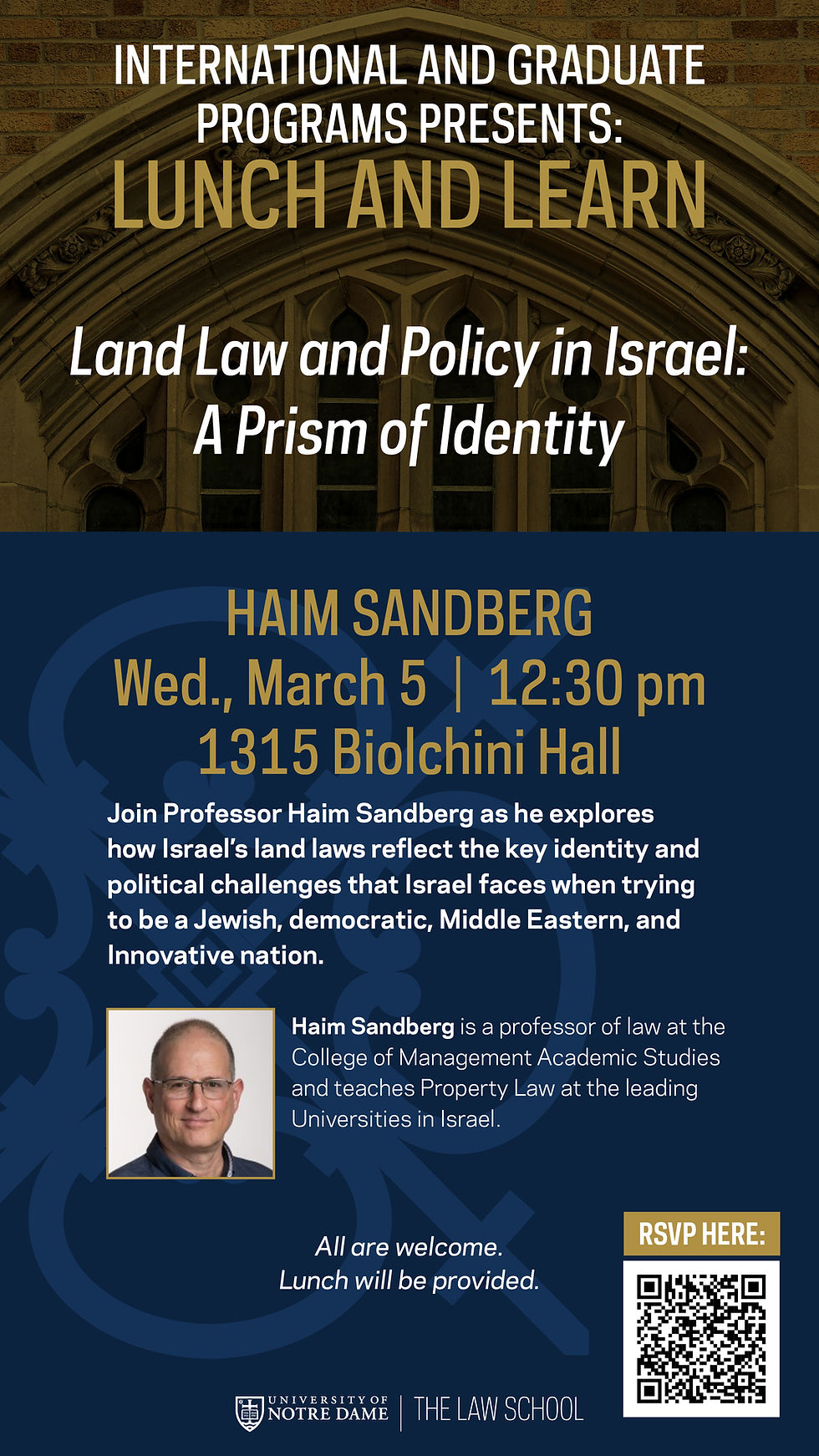

- Haim Sandberg

- Nov 2, 2021

- 19 min read

Updated: Dec 25, 2021

I am proud to share that my chapter Kinship and Commons: The Bedouin Experience will be published next week in The Cambridge Handbook of Commons Research Innovations, edited by Professor Sheila R. Foster and Chrystie F. Swiney from Georgetown University School of Law. This volume reflects the multifaceted and multidisciplinary field of the commons theory, first articulated by Elinor Ostrom, from a variety of perspectives. My contribution challenges a key precondition for many sustaining commons institutions - tight-knit communities. It argues that the gradual transformation of traditional nomadic societies into modern urban societies reflects a major change that has weakened the ability of kinship relations to serve as a social incentive to support sustainable common property regimes resulting in the fostering of a modern urban tragedy of the commons. My chapter illuminates this argument by analyzing theories of social evolution and examining closely the urbanization processes undergone by Bedouin society in Israel, in which tight kinship relations traditionally supported sustainable management of the commons. The urbanization of Bedouin society challenged this traditional regime and triggered the evolution of private urban-style property units, on the one hand, and modern tragedies of the commons, on the other. The chapter raises the question whether societies in which kinship ties have become less powerful can still produce strong enough incentives for collaboration.

***

Kinship and Commons: the Bedouin Experience

Haim Sandberg, Kinship and Commons: the Bedouin Experience in The Cambridge Handbook of Commons Research Innovations 34 - 42 (Sheila Foster & Chrystie Swiney eds., Cambridge University Press 2021).

Strong kinship relations are rooted in tribal social structures and enable the efficient administration of tribal common properties. The clustering of tribal members in urban areas has gradually weakened tribal blood ties and altered the values of traditional tribal society. Modern urban culture emphasizes the autonomy and flourishing of individuals, rather than collective or communal continuity.[1] This change has reduced the power of natural social incentives to support sustainable common property regimes and fostered modern urban tragedies of the commons. Can modern urban society still maintain or redevelop social incentives strong enough to support efficient commons regimes? This is the political question at the heart of the Hardin-Ostrom debate. The main point of disagreement between Garrett Hardin and Elinor Ostrom was whether the contemporary management of public resources should lead to privatization, as Hardin argued, or whether there is an opportunity for effective collective management of those resources, as Ostrom thought.[2] This chapter argues that the tension between these two approaches reflects a larger issue: a major change in human social evolution. The version of the commons conceived of by Ostrom was characteristic of earlier tribal societies, whereas the challenges posed by Hardin better reflect the dissolution of these earlier patterns of human life.

This chapter illustrates this argument through an analysis of the social evolution and urbanization processes experienced by the Bedouin society in Israel. Traditional Bedouin tribes or confederations of tribes are based on kinship relationships. Land resources such as grazing areas, water wells, and convergence sites have traditionally been held in common, rather than as private property. Beginning in the nineteenth century, Bedouin society underwent a process of sedentarization, primarily because of the inability to make a living from grazing. This process had a significant impact on both the Bedouins’ patterns of life and the traditional regime that governed the commonly shared land. The development of agriculture gradually led to the allocation of exclusive property rights, though this process is still incomplete. When more and more Bedouins began to make their living from urban occupations, the movement away from the common property regime accelerated. Yet, the tribal social structure based on strong blood ties still remained in place. urbanization and sedentarization processes did not eliminate the pattern of sharing the commons, but altered them significantly: these patterns went through a metamorphosis.

This chapter first analyzes the debate on the most effective form of property regulation from an evolutionary perspective. Building on the current research literature, it highlights the link between strong tribal kinship relations and sustainable management of the commons. The article then describes how the sedentarization and urbanization of tribal Bedouin society in Israel have affected management of the commons.

Evolutionary Theory and the Commons

The underlying assumption of the theory of evolution is that the purpose of each living species is to assure its genetic survival. Those species that develop the most effective strategies to carry out this mission will ultimately survive and flourish. At times, altruism supplements this genetic drive.[3] For example, when no workers in an ant nest are breeding but they continue to work, biologists give this behavior an evolutionary explanation: the workers may not be contributing to the survival of their own genes, but they are contributing to the survival of the genes of their genetic relative, the queen.[4]

Evolution can explain not only genetic development but also social development. Evolutionists try to explain how different social behaviors, such as parasitism, coexistence, territoriality, or cooperation, promote species survival.[5] King Solomon observed that ants collectively administer their commons "having no chief, overseer, or ruler"[6] and sent his subjects to learn from their ways.[7] Ostrom could certainly base some of her findings on the study of myrmecology.

Humans too have the instinct of living and largely also the instinct of reproduction. According to the evolutionary view, human beings, of course, are subject to the rules of natural selection. Evolution explains physiology and genetics as well as human social behavior patterns.[8] Indeed, the attempt of humanity to give an evolutionary explanation to its own behaviors is somewhat problematic. Human consciousness of the path of evolution, as well as human desires and views, can themselves influence analysis of the evolutionary virtues of our behaviors. Humankind tries not only to make predictions about its future evolution but also to influence it. Despite these interventions, human social behaviors have evolutionary significance. The choice of the form of societal organization have an effect on the survival of individuals, communities, and humankind as a whole.

The scholarly debate on the most effective common property regulation (CPR) is actually an effort both to identify and to influence the path of human evolution. Hardin and Ostrom may have been divided regarding the future of CPR, but they agreed that many societies in the past adopted efficient strategies of commons regulation.[9] They both identified patterns of behavior that characterized early human societies that survived over time. Ostrom based her well-known book, Governing the Commons, on her analysis of institutions that flourished more than a century to more than a millennium ago.[10] She attempted to show that sharing common resources may still be an effective evolutionary strategy, whereas Hardin, in contrast, argued that it should be abandoned.[11]

The debate between followers of Ostrom and supporters of Hardin is really between the advocates of commons regimes and supporters of private property. Critics of the commons see this regime as a barrier to progress and enlightenment. A romantic longing for the past and the natural motivates the supporters of sharing common resources.[12] Both regimes serve an evolutionary purpose by consciously promoting patterns of behavior. However, from a purely descriptive point of view, humankind has so far evolved in a very clear direction—from common ownership to private ownership.[13] If this is indeed the direction of development, this finding requires an evolutionary explanation. Why were effective common strategies the norm in early stages of human development, and why have some communities abandoned these strategies?

Kinship and the Evolution of the Commons

To find the evolutionary explanation for why early societies chose -- and many contemporary indigenous, tribal, and nomadic societies continue to choose -- a commons strategy, we can consult several bodies of research. First, we can look at ethological studies of animal behavior because living cooperatively is not unique to human behavior. In nature, various species evolved systems of coexistence, whereas others live independently. From the biological evolutionary point of view, cooperation prevails when it serves genetic survival. Kin selection is one of the most commonly used mechanisms to produce cooperation, as in the ants example.[14] Likely, humankind chose a common resources strategy for the same reason that ants did: it increased the probability of survival.

Other scientific fields that can help us understand why early humans chose collaborative strategies include ancient archaeology and anthropological research into indigenous or tribal societies. Most ancient human societies, as well as many contemporary indigenous, tribal, and nomadic societies, are organized along common ownership and open-access systems to land resources.[15] We know that the way property was managed in such societies was closely related to their tribal structure. There was overlap between the property structure and the extended family structure. Societies tended to preserve property in a patriarchal or patrilineal manner. In a tribal patriarchal society, retaining lands within the patrilineal ancestor's tribe throughout the generations is considered of prime importance. Owning land is viewed as key to one’s way of life and as an identity marker for the broader clan or tribe as their social unit. Allowing outsiders to own land, whether through a sale or inheritance, weakens not only the economy but also the very fabric of society.[16]

A broad definition of family has shaped adoption of the tribal commons strategies. Sharing resources seems to be directly related to the goal of evolutionary survival.[17] Strong kinship relations, having large families, and intergenerational stability facilitate several important components of sustainable commons, including trust among people, the free transfer of information, and soft enforcement mechanisms.[18] Hardin too assumed that breeding (or "overbreeding") is a Darwinian choice of "Homo Progentivus," calling it "a policy to secure the aggrandizement" of "the family, the religion, the race of the class (or indeed any distinguishable and cohesive group)."[19]

An evolutionary perspective on tribal societies allows us to better understand the reasons why humankind has gradually abandoned sharing as a central strategy of social behavior. The most-cited historical explanation for the change is an increase in population size, which led to increased pressure to obtain essential resources, capitalism, and the transition to a market economy.[20] These changes led to change in social interactions as well. The social basis of sharing in modern urban society is not based on genetics. Modern urban communities are communities of genetic strangers. Once people abandon the tribal lifestyle and move into an urban environment that places at its center the individual or, at most, the small nuclear family unit, the power of the commons, and the ideas it is built upon, are weakened; the connection between cooperation and breeding becomes much less important. In some Western countries, the weakening of kin ties has even weakened the genetic motivation and the social incentive to reproduce, leading to a "demographic transition"; that is, a decline in fertility rates.[21] The trust and social conditions that naturally encouraged cooperation in a tribal society no longer exist in urban settings, where most people are genetically alien to one another.

Such an evolutionary perspective raises questions about the likelihood that approaches to revive the strategy of the commons will succeed. They seek to re-create in modern urban neighborhoods patterns of behavior that worked well in an environment where social norms sanctified kinship relations within an extended family, clan, or tribe. Whether modern urban life can produce human incentives to cooperate that will be as strong as kinship relations and genetics is too early to predict.[22] Indeed, guilds and corporations emerged in Western Europe despite the weakening of kinship relations.[23] There are also examples of some urban communities with strong ties.[24] However, the fate of modern forms of communes, such as kibbutzim, does not augur well for their long-term, sustainable survival.[25] There may be other social modern incentives that encourage social obligations in modern communities.[26] Yet, the chances that humankind will produce collaboration incentives that will be as powerful as kinship relations is at best questionable.[27]

The next section analyzes how both kinship relations and the transition from a nomadic to an urban life affect a group’s strategies toward common resources. It focuses on the Bedouins living in the northern Negev in Israel.

The Bedouin Metamorphosis

Kinship and Tribal Commons. The Bedouins are an ethnic group of nomads living in the deserts of the Middle East and North Africa; they have a tribal structure.[28] Each tribe or group of tribes is considered to stem from one ancestor. This social structure fits well with both the evolutionary rationale of genetic reproduction and survivability.[29] Bedouins traditionally made a living from raising camels and grazing sheep. They held land resources, mainly water wells and pasture, in common. Each tribal confederation provided its members with equal access to these resources and in certain circumstances would permit such a grant to members of other tribal federations.[30] This regime of the commons was motivated by survival: Bedouins, who had a common genetic background, shared this quest to survive.[31] In Bedouin society, there were conditions that supported a regime of common ownership, such as those enumerated by Ostrom: trust among blood relatives, tribal independence, and tribal tribunals that resolved disputes.[32] However, like many traditional societies, it had to confront changes that challenged the long-standing commons strategy

Sedentarization and Urbanization. The common ownership regime in the Bedouin community living in the Negev region in southern Israel has undergone change over the past century. The community numbers about 270,000 people, comprising about fourteen percent of Israel’s Arab population and about 3 percent of the total Israeli population.[33] At the end of the nineteenth century, the Bedouins population began to experiment with agriculture because of the difficulty of making a living exclusively from the traditional raising of livestock. This change resulted in an internal allocation (not recognized by the government) of private and noncommon property rights, but only in cultivated agricultural areas.[34] It did not affect the open-access regime that prevailed in the rest of the territories of the tribal confederation. In addition, the private agricultural land was also kept within a tribal framework; when land was sold, the first right of purchase was reserved for members of the tribe, especially neighbors of the previous owner.[35] Some of the Arab agricultural villages in Israel are also organized in this manner.[36] In both Arab and Bedouin societies, the allocation of private property rights in agricultural land is still, albeit more loosely, linked to broad family patrilineal relations, reflecting the evolutionary quest for genetic survival.

The establishment of the State of Israel brought two changes that challenged the traditional mechanism of common ownership. First, most of the Bedouins had to leave their original territories and were relocated by the state in land near Beer Sheva that was designated for their new settlement (the Sayag area).[37] Second, both the nomadic grazing way of life and the sporadic agriculture that began in the nineteenth century ceased to be the main sources of income for the Bedouins, and they began to make their living by pursuing urban occupations such as providing services or trading.[38] Bedouin populations in other Middle Eastern countries have undergone a similar process of sedentarization.[39] These changes forced the Bedouin society as well as the State of Israel to adapt the old traditional proprietary system to these new circumstances. Because strong kinship and tribal relationships encourage the tendency to share common land and resist privatization, this trend toward sedentarization produced new patterns of behavior. Weakening this tribal structure can lead to chaos and harm the incentive to cooperate.

Remains of the Commons in New Towns. The threats to their traditional style of life led more than half of the Bedouin population to seek permanent settlement in the small towns created by the State of Israel for their resettlement. In these towns, each family was given the private property right to a residential plot.[40] The transition from a nomadic and open-space regime to a regime of private urban property was fraught with difficulties: many of the Bedouin found it hard to adjust to an urban way of life. Today, these towns and their populations have some of the lowest rankings on combined socioeconomic indices in Israel. [41]

However, in some of these state-established towns, certain neighborhoods are made up of residents only from a single Bedouin tribe, while other neighborhoods contain a mixed population including members of different tribes. Neighborhoods with a homogeneous tribal population have developed a version of “urban tribalism,” maintaining traditional patterns of common area management in public urban spaces. Residents of neighborhoods with a mixed population have not maintained a common interest in similar public urban spaces.[42]

The state made a similar attempt to resettle Bedouins in northern Israel, where their adaptation to modern patterns of settlements has been more successful.[43] One of the reasons for this smoother adaptation was stated by a Bedouin in the north in a recent television interview when he stated, "[w]e are no longer Bedouins."[44] The property changes in northern Israel thus, in some cases, led to a change in group identity.[45] Bedouins in other countries in the Middle East have gone through a similar process of "detribalization" in which an overall Bedouin identity—one based on a common history and subculture—replaced the strong tribal boundaries of blood ties. In these societies communal rights are no longer recognized.[46]

In new towns, tribal blood ties may continue to be, at least for a while, an incentive for the effective management of common resources, even when the entire environment changes. When tribal tradition and blood ties loosen, the ability to cooperate weakens, and adaptation to a private property regime improves.

Spontaneous Tragedy of the Commons. Nearly half of all Bedouins have refused to move to towns and cities. On land that they consider to be their common grazing territory, they have begun independently to build unplanned residential constructions, mainly tin shacks. They are thus using open-access land for residential purposes. Such constructions preserve some of the characteristics of the traditional neighborhoods, but have slowly become more permanent.[47] These settlements of shacks spread quickly, occupying very wide areas of the open spaces.[48] They are a clear example of Hardin's tragedy of the commons.

Bedouins see these "spontaneous settlements" as a way to protect their land.[49] They demand that the government legally recognize them and invest in their development. Yet the government considers them to be illegal because they are being built without the necessary public infrastructure and do not meet urban construction standards. The government wants in principle to stop the expansion, but it has not acted decisively toward this goal. It prefers negotiating with the Bedouins and has even considered legalizing some of their settlements.[50]

The Bedouin response to their dispersion indicates again that common open-access patterns that were developed in traditional or nomadic societies do not suddenly disappear when there is a change in the circumstances of life. Traditional attitudes to common resources drive the creation of new versions of common resources as long as there are no governmental barriers and traditional kinship relations prevail in the changing society.

Claiming Commons as Private. Another strategy adopted by a small portion of the Bedouin who remain in their original territories is to file lawsuits for recognition of private property rights to their former open-access territories. They claim private property rights to an area of about 650 square kilometers.[51] For the sake of comparison, the entire urban built-up area of the State of Israel (excluding the Bedouin dispersion area), was about 840 square kilometers in 2003 and 900 square kilometers in 2007.[52] The entire area that is privately owned in the State of Israel is about 1,500 square kilometers.[53] The government opposes the Bedouins’ lawsuits and claims that they have no legal basis. The Supreme Court rejected them, inter alia, on the grounds that collective rights cannot be given to individuals.[54] That the Bedouins have made these claims illustrates their adherence to the common-access traditional order while adapting to the newer and completely different standard of private property through legal means. The underlying motivation of both is keeping land assets within kinship groups.

Conclusion

This chapter focused on the role of kinship relations in the effectiveness of strategies for the management of common resources. This linkage is not only well known in legal writing about the commons but is also recognized in the literature dealing with the social evolution of nonhuman species and humankind and with the social structure of tribal societies. It reflects a strategy of social and genetic survival. Modern processes of urbanization and sedentarization have severed blood ties, so that urban societies usually comprise genetic strangers. The loosening of blood ties or their lack thereof weakens the incentives for sharing in a modern urban society and causes tragedies of the common. The political debate between Ostrom and Hardin deals with how to respond to this change in human evolution.

The importance of traditional kinship relations in fostering cooperation can be seen in modern Bedouin society in Israel, which has undergone both sedentarization and urbanization. These processes have led to the abandonment of the traditional regime of the commons; they also show how difficult it is for a tribal society to break away from the commons tradition and adapt to urban private ownership patterns. The tribal structure based on close blood ties still remains, if weakened. Traditional sharing patterns continue to influence attitudes to open and urban space held by residents of newly created towns in the south of Israel; however, this effect varies by the composition of the neighborhood.

In segregated Bedouin urban neighborhoods, there is a high degree of sharing common resources, but the weakening of tribalism has impaired the ability of Bedouins living in mixed urban neighborhoods to collaborate on public spaces. Among those Bedouin who have chosen to erect encampments on large tracts of grazing lands, some are waging lawsuits to claim them as privately-owned areas. At the same time, Bedouins who have settled in the north of the country seem to have a stronger capability to adapt to an individualistic urban lifestyle.

The significant contribution of blood ties to common resource management raises the question of whether societies in which kinship ties have loosened can produce strong enough incentives for collaboration. The answer to this question poses serious challenges for both Hardin's and Ostrom's models.

[1] Gregory S. Alexander, Property and Human Flourishing (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), 4–9. [2] Garrett Hardin, “The Tragedy of the Commons,” Science 162, (1968): 1243, 1247; Elinor Ostrom, Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action (Cambridge University Press, 1990), 216. [3] William Donald Hamilton, Narrow Roads of Gene Land: Evolution of Social Behavior (Basingstoke, W. H. Freeman at Macmillan Press Ltd., 1996) 19, 31–32. 4 Andrew F.G. Bourke and Nigel R. Franks, Social Evolution in Ants (Princeton University Press, 1995), 26–27. [5] “Social Evolution—Latest Research and Reviews,” Nature, accessed September 9, 2018, https://www.nature.com/subjects/social-evolution. [6] Proverbs 6:7. [7] Proverbs 6:6 (“Go to the ant, thou sluggard; consider her ways, and be wise”). [8] Jack Hirshleifer, “Economics from A Biological Viewpoint,” Journal of Law and Economics 20, no. 1 (1977): 7–9. [9] David B. Schorr, “Savagery, Civilization, and Property: Theories of Societal Evolution and Commons Theory,” Theoretical Inquiries in Law 19, (2018): 507, 524. [10] Ostrom, supra note 2, at 58. [11] See citations, supra notes 2. [12] Schorr, supra note 9, at 524. [13] Harold Demsetz, “Toward a Theory of Property Rights,” American Economic Review 57, (1967): 347, 350–353; Robert Ellickson, Order Without Law: How Neighbors Settle Disputes (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991), 184; Daniel Fitzpatrick, “Evolution and Chaos in Property Rights Systems: The Third World Tragedy of Contested Access,” Yale Law Journal 115, (2006): 996, 1010, 1011–1012. [14] Daniel J. Rankin, Katja Bargumand, and Hanna Kokko, “The Tragedy of the Commons in Evolutionary Biology,” Trends In Ecology & Evolution 22, (2007): 643, 648; F. L. W. Ratnieks et al., “Conflict Resolution in Insect Societies,” Annual Review of Entomology 51, (2006): 581, 584; T. Wenseleers and F. L. W. Ratnieks, “Tragedy of the Commons in Melipona Bees,” Proceedings of the Royal Society–Biology Science 271, (2004): 310, 312. [15]Henry Schaffer, Hebrew tribal economy and the Jubilee (New York: G. E. Stechert & Co., 1922), III–V (A conclusion based on a comparative study of ancient Hebrew, pre-Islamic, Indian, Homer, Roman, Russian, German, Irish, Welsh, and English tribal societies); RuchaGhate et al., “Cultural Norms, Cooperation, and Communication: Taking Experiments to the Field in Indigenous Communities” International Journal of The Commons 7, (2013): 498, 501; Samira Farahani, “Ecological Engagement in Tribal Communities in the Context of Common-Pool Resources” (MA thesis, Texas State University, May 2018), 22, 38, 42. [16] Numbers 27:1-11, 36:1-12; Schaffer, supra note 15, at 98–99; Jeffrey A. Fager, Land Tenure And The Biblical Jubilee (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1993), 27–34; John Sietze Bergsma, The Jubilee From Leviticus To Qumran: A History of Interpretation (Leiden; Boston: Brill Academic Publishers, 2007), 8–12; Fitzpatrick, supra note 13, at 1028–1029. [17]Joseph Henrich and Natalie Henrich, Why Humans Cooperate: A Cultural and Evolutionary Explanation (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 89–107. [18] Ostrom, supra note 2, at 88; Schorr, supra note 9, at 525. [19] Hardin, supra note 2, at 1246. [20] Schorr, supra note 9, at 529. [21] Lesley Newson et al., “Why Are Modern Families Small? Toward an Evolutionary and Cultural Explanation for the Demographic Transition,” Personality And Social Psychology Review 9, (2005): 360, 370–372 (Indicates the link between the lack of support for reproduction on the part of a broad family framework and the decline in reproduction rates); John C. Caldwell, “Demographic Theory: A Long View,” Population and Development Review 30, (2004): 297, 303 (Analyzes theoretical explanations for low fertility rates, some of which are based on “the fact that post-agricultural society did not need the traditional family”). [22]Alexandra Flynn, Below Ch.7, at 131. [23] Tine De Moor, “The Silent Revolution: A New Perspective on the Emergence of Commons, Guilds, and Other Forms of Corporate Collective Action in Western Europe,” International Review of Social History 53, (2008): 179, 211. [24] Stephen Glackin, “Contemporary Urban Culture: How Community Structures Endure in an Individualized Society,” Culture and Organization 21, (2015): 23, 34–39; Lucie Middlemiss, “Individualized or Participatory? Exploring Late Modern Identity and Sustainable Development,” Environmental Politics 23, (2014): 929, 933–941. [25] Abraham Bell and Gideon Parchomovsky, “Property Lost in Translation,” University of Chicago Law Review 80, (2013): 515, 520. [26] Alexander, supra note 1, at 109–113. [27] Gideon M. Kressel, Descent Through Males: an anthropological investigation into the patterns underlying social hierarchy, kinship, and marriage among former Bedouin in the Ramla-Lod area (Israel) (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1992), 254–255; Tamas David-Barretta and Robin I. M. Dunbar, “Fertility, Kinship and the Evolution of Mass Ideologies,” Journal of Theoretical Biology 417, (2017): 20, 24–25. [28] Austin Kennett, Bedouin Justice: Law and Custom among the Egyptian Bedouin (London: Cass, 1968), 1–12. [29] Emanuel Marx, Bedouin of the Negev (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1967), 63. [30] Emanuel Marx, “The Tribe as a Unit of Subsistence: Nomadic Pastoralism in the Middle East,” American Anthropologist 79, (1977): 343, 348–349; Clinton Bailey, Bedouin Law From Sinai & The Negev: Justice Without Government (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009): 263–264. [31] Kressel, supra note 27, at 242–249. [32] Bailey, supra note 30, at 16–22, 158. [33] Israel Central Bureau of Statistics, Table 2.1: Population by population group & Table 2.15: Population by district, sub-district and religion, Statistical Abstract of Israel (2019). [34] Gideon M. Kressel et al., “Changes in the Land Usage by the Negev Bedouin since the Mid-19th Century: The Intra-Tribal Perspective,” Nomadic Peoples 28, (1991): 28, 31–40; Bailey, supra note 30, at 268. [35] Bailey, ibid, at 269; Kressel et al., ibid, at 40. [36] Rassem Khamaisi, “Housing Transformation within Urbanized Communities: The Arab Palestinians in Israel,” Geography Research Forum 33, (2013): 184, 190–200; Rassem Khamaisi, “Land Ownership as a Determinant in the Formation of Residential Areas in Arab Localities,” Geoforum 26, (1995): 211, 215–216. [37] Havatzelet Yahel and Ruth Kark, “Israel Negev Bedouin during the 1948 War: Departure and Return,” Israel Affairs 21, (2014): 48; Ghazi Falah, “The Spatial Pattern of Bedouin Sedentarization in Israel,” Geojournal 11, (1985): 360. [38] A. Allan Degen and Shaher El-Meccawi, “Livestock Trader Entrepreneurs among Urban Bedouin in the Negev Desert,” Entrepreneurship and Innovation 9, (2008): 93, 95; Shaul Krakover, “Urban Settlement Program and Land Dispute Resolution: The State of Israel versus the Negev Bedouin,” Geojournal 47, (1999): 551. [39] Donald P. Cole, “Where Have the Bedouin Gone?” Anthropological Quarterly 76, (2003): 235, 240–251; Nancy A. Browning, "I am Bedu: The Changing Bedouin in a Changing World" (MA diss., University of Arkansas, 2013), 33-40; Andrew Shryock "Bedouin in Suburbia: Redrawing the Boundaries of Urbanity and Tribalism in Amman" The Arab Studies Journal 5, (1997): 40, 42, 29; 302, 311-313; Riccardo Bocco, "The Settlement of Pastoral Nomads in the Arab Middle East: International Organizations and Trends in Development Policies, 1950-1990" Nomadic Societies in the Middle East And North Africa: Entering the 21st Century (Dawn Chatty ed., Brill 2006): 302, 311-312. [40] Havatzelet Yahel, “Land Disputes between the Negev Bedouin and Israel,” Israel Studies 11, (2006): 1, 5, 13. [41] Israel Central Bureau of Statistics, Table 1: Socio Economic Index 2015 of Local Authorities in Ascending Order of Index Values—Index Value, Rank and Cluster, https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/mediarelease/doclib/2018/351/24_18_351t1.pdf. [42] S. Tamari et al., “Urban Tribalism: Negotiating Form, Function and Social Milieu in Bedouin Towns, in Israel,” City Territory and Architecture 3, (2016): 1, 9–10; Yuval Karplus, “The Dynamics of Space Construction among the Negev Bedouin” (PhD diss., Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, 2010) (Hebrew), 239–241. [43] Arnon Medzini, “Bedouin Settlement Policy in Israel: Success or Failure?” Themes in Israeli Geography 79, (2012): 37, 43–44. [44] Gil Karni and Peleg Nathaniel, “Second Look: Permanent House for Nomads—On the Northern and Southern Solution to the Bedouin Localities,” Kan 11: Israel Broadcasting Corporation, YouTube video, 6:57, February 13, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1FLE8-wk-oI (Hebrew). [45] Arnon Medzini, "Tribalism Versus Community Organization: Geography of a Multi-Tribal Bedouin Locality in the Galilee", Studia z Geografii Politycznej i Historycznej 5 (2016): 237, 251-253. [46] Cole, supra note 39, at 250–252; Browning, supra note 39, at 37. [47] Isaac A. Meir and Ilan Stavi, “Evolution of the ‘Modern’ Transitory Shelter and Unrecognized Settlement of the Negev Bedouin,” Nomadic Peoples 15, (2011): 33, 35, 41. [48] Yahel, supra note 40, at 4–8. [49] Falah, supra note 37, at 367. [50] Deborah F. Shmueli and Rassem Khamaisi, “Bedouin Communities in the Negev: Models for Planning the Unplanned,” Journal of the American Planning Association 77, (2011): 109, 115; Yahel, supra note 40, at 11–13. [51] Yahel, supra note 40, at 8. [52] Amir Eidelman and Yael Yavin, “Built Areas and Open Spaces in Israel,” in Israel Sustainability Project 2030: Indices—Sustainability Yesterday, Today And Tomorrow (Israeli Ministry of the Environment, 2011), 3 (Hebrew); Moti Kaplan et al., Patterns of use of Built-Up Areas in Israel (2007), 89 (Hebrew). [53] Israel Land Administration, Report on Activities for the 2012 Budget Year (2013), 72 (Hebrew). [54] C.A.4220/12 “Al-Uqbi v. The State of Israel,” J. Hayut, par. 36, 42, 67, 81 (May 14, 2012) (Official English translation), https://supremedecisions.court.gov.il/Home/Download?path=EnglishVerdicts\12\200\042\v29&fileName=12042200.V29&type=5.

Comments